Witness + two masters who created the history of images

[Tao Ting Pictures] Graphic Novel Column

Since the 20th century in the United States, the development of graphic novels has had its key moments and key figures. Two of the important promoters happened to be Jewish: Will Eisner (1917-2005), known as the godfather of American animation, and Art Spiegelman (1948-) was the first to advance graphic novels into educational and cultural circles.

Will Eisner

Eisner is a globally recognized master of comic art. His long life and creation can be said to be the epitome of the development of American graphic novels.

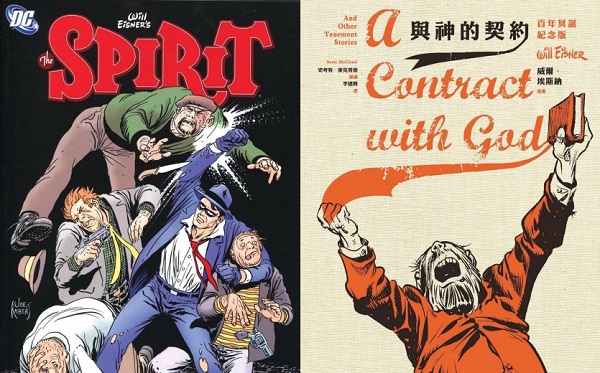

At the end of World War I, Eisner was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York City. He loved graffiti since he was a child. As a teenager, he was the main contributor to school magazines and yearbooks. In the late 1930s, the young Eisner came across the infancy of Superman comics, and set up a studio with his friends to devote himself to this field. In 1940, the original "The Spirit" (The Spirit) was published for more than ten years and became popular all over the world. Compared with subsequent Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man, The Flash, the New York detective who survived the catastrophe, is more down-to-earth and has a Jewish sense of humor. Eisner refined his skills to develop the story, taking advantage of comics' hand-lettered text and full-page splash art.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, after retirement, Eisner shifted the focus of the studio to educational and commercial cartoons, and drew a large number of technical guides for the military. In the early 1970s, when he was over 50 years old, he came into contact with experimental comic works led by Spiegelman. Industry veteran Eisner was deeply inspired to rethink another possibility of the comics medium.

When Eisner released "A Contract with God" in 1978, he called it a "graphic novel" in order to differentiate it from the traditional serialized Superman comics that were mainstream at the time. ). Despite the twists and turns in the publishing process, this work was finally released, and the name of the graphic novel also raised its flag and entered the publishing world and the public eye.

"Contract with God" is Eisner's attempt to break through in content and theme after his skills matured. He wanted to explore: As a narrative art that complements pictures and text, can graphic novels break away from the public's stereotype of comics - formulaic Superman comics with boys as the main audience - and show serious concern?

The four short stories are all set in the fictional "55 Dropsey Avenue" affordable apartment in the Bronx, New York during the Great Depression of the 1930s, showing the joys and sorrows of Jewish and other ethnic immigrants in the slums. Later, "A Life Force" (1988), also set on Drapsey Avenue, used the comparison between humans and cockroaches to repeatedly examine the meaning of survival: What else is there besides survival? What is the connection between daily necessities, rice, oil, salt and poetry and the distant place? He said of himself: "Born and raised in New York City, and raised there, I carry many memories, some painful and some happy, locked in the warehouse of my mind. I want to share them like an ancient sailor. My accumulated experiences and observations. If you like, I am a graphic witness who reports on life and death, heartbreak and the endless struggle to win...or at least survive.”

Since the 1980s, Eisner has successively created more than a dozen original graphic novels with different themes. In his later years, he adapted classics such as Don Quixote and Moby-Dick into comics. In addition to his lifelong involvement in various types of comic creation, he is also committed to teaching and theoretical research. "Comics and Sequential Art" (1985) and subsequent works are based on his many years of teaching comics creation at the School of Visual Arts in New York. They are still irreplaceable books on comics theory and application. The most important award in the animation industry, the "Eisner Award" founded in 1988, is named after him. His overall contribution to graphic novels is still unmatched by anyone.

▲The painting style of Eisner's superhero "The Shining" and the theme of "Contract with God", which raised the banner of the graphic novel, are both groundbreaking masterpieces.

Art Spiegelman

Spiegelman's parents were Jews who settled in Poland. They were sent to Nazi concentration camps during World War II. At the end of the war, most of the family died, including their eldest son. After the war, his parents moved to Sweden, where Art was born. He immigrated to Pennsylvania in the United States when he was three years old, and moved to Queens, New York City when he was nine.

Similar to Eisner, he loved comics since he was a child. When he graduated from high school, his parents encouraged him to pursue a lucrative career as a dentist, but he chose to study art and philosophy at a small college. In 1968, due to mental instability, he dropped out of school and was hospitalized. When he was discharged from the hospital, he received the tragic news that although his mother had escaped the concentration camp physically, her mind had been tortured by the ghost of war and depression for many years, and she finally collapsed and committed suicide. After the death of his biological mother, the relationship between father and son dropped to a freezing point. He traveled to San Francisco and abused drugs to anesthetize his inner pain. At the same time, he actively participated in the underground comics movement and created many avant-garde and bold works in both style and content.

In the mid-1970s, Spiegelman returned to New York and co-founded and edited the avant-garde comics magazine "Raw" with his French-American wife. He is also a contributing editor and cartoonist for The New Yorker magazine. After settling down, he reconnected with his father and asked about his father's experiences in the first half of his life, paving the way for the creation of "Rat Tribe".

Maus

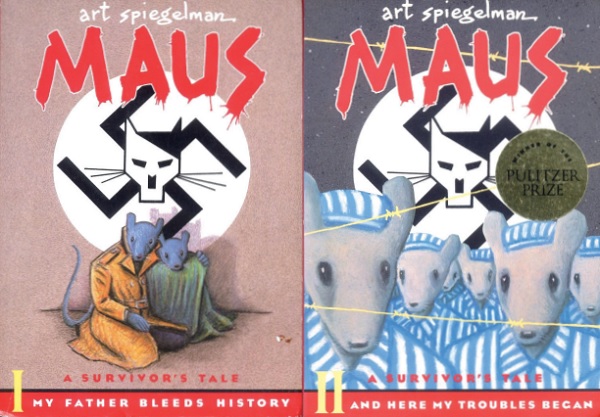

The first two volumes of "Maus" were serialized and then published from 1980 to 1991. Controversies continued after its publication, but it is the only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize so far. Translations in more than 30 languages have sold tens of millions of copies in the United States alone; many high schools and universities have selected it as a designated reading for literature or history courses; related paintings have been exhibited in museums and art galleries around the world. It would not be an overstatement to say that "Maus" gave birth to a new serious perspective on long-form graphic documentary literature in North American academic, educational, artistic and literary circles.

Writing over a period of eight years, Spiegelman recorded the story of his father's struggle for survival in his youth in a sincere and low-key manner. My parents were witnesses to the catastrophe in Europe during World War II. During the Nazi German rule in Poland, their experiences of inhuman treatment and their desperate attempts to escape from the concentration camps were deeply moving.

Intertwined with the past is the current story line - Spiegelman outlines the present tense in the same restrained tone - the father's stinginess and unreasonableness drove people around him, especially his stepmother and only son Spiegelman, crazy; the biological mother in history Bigman's tragic suicide as an adult; how the icy relationship between father and son for many years is mysteriously melting away bit by bit in revisiting the sad memories...

In terms of artistic expression, the most unique part of "Maus", and the most controversial part when it was released, is that the author painted Jews as rat faces, while (Nazi) Germans and Poles were painted as cats and pigs. The use of anthropomorphic animals as protagonists to express heavy historical themes has brought controversy, but its shock and influence are unprecedented.

In "Maus", different ethnic groups wear animal masks that can determine the fate of life and death. Interestingly, in the first volume, the Jewish people look like rats with human bodies, but in the second volume, there are several scenes where the characters wear rat masks. In addition to outlining ethnic masks, Spiegelman also reminds readers of the common humanity beneath the faces of different cultures and ethnicities. Therefore, in "Maus", an in-depth experimental work supported by extensive documentary research and first-hand interviews, the cat and mouse masks go far beyond the superficial skin of cartoons and have multiple symbolic meanings.

The artist Spiegelman performed his autopsy. After the first volume was published, the second volume was supposed to be released quickly. However, many years passed in time. It was not until he put on a mask for himself in his heart and creation that he could once again enter into his father's oral history and describe it. The horrific experiences of our ancestors in Auschwitz. For readers, excluding the detailed features of human faces and facing the faces of animals, it is also helpful to read "horrible" scenes and deepen their recognition of the common human experience.

Taiwanese-American scholar Liu Wen has a fair evaluation of "Maus":

"Creation for Art goes beyond recording the moments of historical trauma, but as Senior Shi Ming said: 'Being a good person.'... To find the value of one's own survival, in addition to one's own sorrow, one can also There is a basic concern for things and people in the world.

⋯⋯The purpose of presenting "Maus" in comics is not to trivialize the massacre. On the contrary, this is a story that can only be expressed through images. It not only reflects the ultimate expression of racial discrimination, but also creates a fantasy imagination space that transcends time and space. Therefore, "Maus" is not only the history of the Jews, but a symbol of any oppressed ethnic group. In the image of the cat chasing the mouse, we can reflect on our own trauma and that as a former oppressed, we may also become the next group to oppress others. "

Using mice to represent the Jews and cats to represent the Gestapo seem to animalize the nation and simplify complex history. But under the author's superb expression, it has become a symbol of multiple meanings and multiple levels. Wearing an animal mask also allows the author to tell this extremely painful and extremely private story. "Maus" is not a big historical narrative, but a family story of a father and son. During the writing process, Spiegelman only wanted to faithfully tell the story of his father and himself; he had no original intention of turning the world around with this book, nor did he expect that the book would have such a large and long-term readership. The endless applause from readers from generation to generation pays tribute to him for raising the bar of art and documentary literature.

▲ Spiegelman's "Maus" has been controversial since the two volumes were published, but it is the only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize.

Double walls shine

Both are the standard-bearers of contemporary American and even world graphic novels. Eisner and Spiegelman have many things in common:

1. Connecting New York City and Creation

Both authors have spent most of their lives in New York City, an art town, and their main works also depict urban characters. In his later years, Eisner further made the slum apartments in "Contract with God" and "Vital" the focus of his new book "Dropsy Avenue" (1995), presenting the century-old urban and rural transformation from 1870 to 1970 from a slice perspective, representing Generations of immigrants have different backgrounds but have similar blind spots and struggles.

American supercomics usually use characters or plots to drive the story. Eisner and Spiegelman proved to readers that the "scene" in graphic novels is also a major literary element. Pure text novels must use words to describe scenes, while graphic novels can be directly presented under the outline of a painter. This gives Eisner and Spiegelman many possibilities to recreate the city where they have lived for many years and where they love and hate.

2. Cultivate the new generation

The two masters not only elevated graphic novels to the status of serious literature with their original works, but also devoted themselves to promoting the graphic novel "movement." The two have taught classes at the School of Visual Arts in New York for many years, cultivating a batch of new generation cartoonists. Eisner's "Comics and Comic Art", which he wrote for teaching needs, remains a classic; the pioneering comic magazine edited and published by Spiegelman and his wife was the first publication ground for many creators who later became successful. Perhaps because of the marginalized status of comics that has not been recognized for many years, this group of creators who are diligent in breaking through the limitations of old prejudices have gathered into a literary community as long as there is a suitable leader and a field, and they have learned from each other, which has promoted the popularity of graphic novels in the past three decades. It bloomed everywhere in ten years.

3. Reflect the historical and divine views of the Jewish background

Perhaps related to the ancient Jewish national background, the works of Eisner and Spiegelman have strong historical concerns. Both are descendants of European immigrants, and are particularly concerned about immigrants, especially the difficulties experienced by disadvantaged immigrants in new countries. Is the rich cultural heritage of the immigrant’s home country a treasure or a burden in the new country? Although the stories are expressed in different ways, the collision between microscopic history and macroscopic history is indeed a theme often explored in their works.

In addition to historical concerns, some of their works also have theological concerns. The God Jehovah is not completely absent in the story, but he is often distant from the characters, even indifferent. Eisner's "Dropsy Avenue Trilogy" focuses more on the main characters' questioning and rage against God. Spiegelman's "Maus" objectively depicts the influence of Jewish faith in his father's generation. Jehovah is the God of Abraham, Jacob, and Isaac, and is the god of his father, Spiegelman. In his generation, he is still the God of Ya Spiegelman's own god?

There is no doubt that the fault lines in family beliefs since the mid-20th century have been reflected in literary and artistic works of various ethnic backgrounds. But it also raises expectations. If more new generation graphic novelists who adhere to their Christian faith emerge in the future, will new works have a chance to make up for these gaps?

4. Break through artistic tradition

Eisner’s masterpiece draws from the familiar immigrant landscape of his upbringing. He sees himself as a witness of images, with a realistic painting style, an innovative grasp of frames (size, shape, presence or absence...), and a pioneer in exploring full-page frameless artistic effects. The text and pictures of a good graphic novel are an organic whole and are difficult to evaluate individually. However, many of Eisner's stories are still wonderful stories when separated from the text themselves - they have the condensed realism style of Faulkner and Hemingway, as well as the The heartwarming core of O. Henry's short stories. The mutual adjustment of refined words and images that can ignite emotions is the unique charm of Eisner's works.

In "Maus", Spiegelman restrained the heavy-handedness of the avant-garde works of his youth, and his painting style became restrained and restrained. Animal faces replaced human faces, ostensibly easily resolving the heavy theme of ethnic cleansing in World War II. However, as I read page by page, the story becomes more and more attractive, the complexity of the characters becomes more and more apparent, and the sound is still lingering after I close the book. He bravely dug into his bumpy interactions with his father, his struggle with the history of blood and tears of the Jewish people, and his doubts and efforts about how much art can restore the stories of the previous generation... "Maus" is not only a painting of memories of two generations, but also an unprecedented use of pictures and text to create a bridge to the depths of human nature.

Eisner and Spiegelman both have the sense of mission and ambition of historical storytellers: without drawing these stories, Eisner's growth and the blood and tears of Spiegelman's parents in the concentration camp will be annihilated. From different angles, they paid attention to the history of individuals, families, and communities; the classic works they drew and wrote promoted the historical development of graphic novels. If Eisner and Spiegelman were both absent, we can safely say that graphic novels in the United States and even the world would not be the scene where a hundred flowers are blooming today.

Huang Ruiyi, holds a bachelor's degree in library science from National Taiwan University and a Ph.D. in Chinese education from Ohio State University, specializing in children's and adolescent literature. He has worked in public and private primary and secondary schools in Southern California for many years. He is currently the director of the International Student Department of Youxi Christian School and a senior staff member and teacher of Genesis Literary Training Bookstore. Articles are scattered in Taiwan and North American Christian publications. In the past eight years, he has been the author of two columns, "Awkward Youth Travel" and "Building a Book Bridge over Bad Water" in Taiwan's "Campus" magazine. Participated in the Fairy Tale Lecture Series of the Far Eastern Broadcasting Corporation. I continue to expand my reading horizons with my two older children who love to read.

Huang Ruiyi, holds a bachelor's degree in library science from National Taiwan University and a Ph.D. in Chinese education from Ohio State University, specializing in children's and adolescent literature. He has worked in public and private primary and secondary schools in Southern California for many years. He is currently the director of the International Student Department of Youxi Christian School and a senior staff member and teacher of Genesis Literary Training Bookstore. Articles are scattered in Taiwan and North American Christian publications. In the past eight years, he has been the author of two columns, "Awkward Youth Travel" and "Building a Book Bridge over Bad Water" in Taiwan's "Campus" magazine. Participated in the Fairy Tale Lecture Series of the Far Eastern Broadcasting Corporation. I continue to expand my reading horizons with my two older children who love to read.